Speaking to avant-garde music devotees in Germany in 1984, composer Morton Feldman delivered a mischievous provocation, almost a warning. “The people who you think are radicals might really be conservatives,” he said. “The people who you think are conservative might really be radical.” Feldman then hummed a section of a symphony by an ostensibly old-fashioned forebear, the proud Finn Jean Sibelius. suryaqq

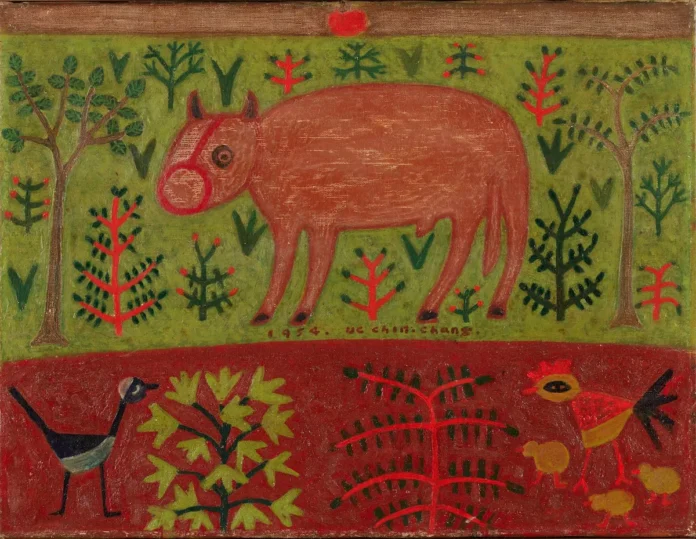

That story came to mind while soaking in the Chang Ucchin retrospective at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art’s Deoksugung Palace branch in Seoul during the last days of summer. Its four galleries are jam-packed with some 300 pieces by the 20th-century painter, who “became almost a mythic figure in Korea,” as art historian Hong Sunpyo writes in the show’s robust catalogue. Depicting tranquil, harmonious, sometimes dreamy scenes of rural Korea with an economy of marks on a flat plane, almost all the pieces charm. Birds fly in a row through the sky. Trees stand proud. People peer from tiny houses. At first glance, they could be the work of a very good illustrator of books for young children.

Keep looking. These seemingly simple, modest size paintings (generally only a little larger than a sheet of paper) are potent—and yes, radical—born of tough, self-imposed restraints. As his native South Korea went through seismic political and economic changes, and as peers like Kim Whanki and Yoo Youngkuk ventured into thrilling abstract terrain, Chang honed his language to absolute essentials. He rendered eyes with just two dots or circles, and people frequently as just stick figures or a precise stain of paint. For decades, he stuck largely to the same few subjects: humans (many of them children) and animals outside in the world, together, at peace. suryaqq

Chang was singular, uncompromising. “When people talk about my paintings, they often comment that they’re too small,” he once wrote. But as he saw it, “as the scale increases, the painting starts to get diluted.” In 1951, as he was entering his mid-30s, he painted an indelible self-portrait on paper (the Korean War had made canvas scarce) about the size of a postcard. It seems to announce both the style that he would pursue for the next 40 years and himself as a major but idiosyncratic talent. He is in the foreground, debonair in a suit and tie (his wedding attire), on a road that stretches far behind him into hills that vibrate with minute gold and green strokes. A black dog follows him, and four blue birds fly overhead. With a top hat and an umbrella in his hands, he suggests a man ready for a leisurely stroll or, perhaps, to open a variety show. Either way, you can hear him calling for you to join him.