Pussy Riot is generally referred to as a punk rock band and performance art ensemble. But at least as it appears in Montreal, the group’s first museum survey does not disclose much in the way of musicality or visual sophistication—except in its brilliantly cacophonous exhibition design. Anyway, such qualities might be beside the point. nikmatqq

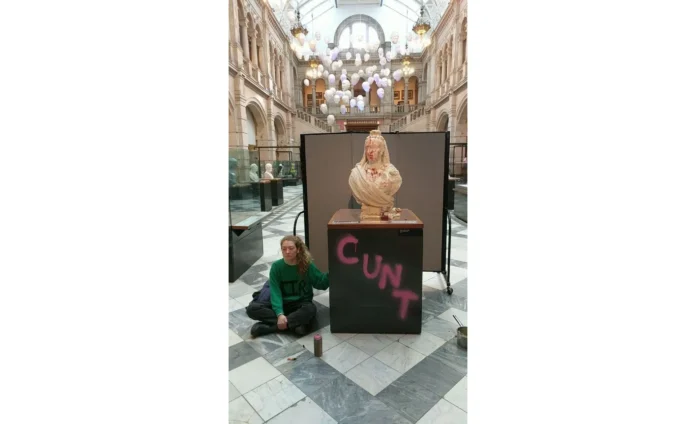

A sort of retrospective in the form of a colorful multimedia show that originated at Kling & Bang in Reykjavik before traveling to the Louisiana Museum of Art, followed by overlapping iterations in Montreal and at the Haus der Kunst in Munich and the Polygon Gallery in Vancouver, “Velvet Terrorism” doesn’t put much stock in subtlety or nuance either. More in the group’s style is a video installed near the exhibition’s entrance, showing a ski-masked Pussy Riot member pissing on a portrait of the Russian president; if that doesn’t make things clear enough, the title of one of the group’s early actions, Fuck You, Fucking Sexists and Fucking Putinists (2011), involved “musical occupations of glamorous venues in the capital” including “areas where wealthy Putinists gather: in Moscow boutiques, at fashion shows, in elite cars, and on the rooftops of Kremlin-affiliated bars.”

Whether or not you’re prepared to enjoy Pussy Riot’s songs as music or their actions and videos as art, though, you’d be hard put to contest their right to the third category into which their work has always been slotted: activism. And yet, after immersing myself in “Velvet Terrorism,” I had to wonder whether even that is quite the right description of what they do. Activism, as I understand it, is not action for its own sake, but is undertaken to achieve some determinate social or political goal, to change the world, or at least one’s country or community. nikmatqq

Is that what Pussy Riot have been up to? Note that the catalog descriptions of their actions are organized into three rubrics: Location, Context, and Reaction—and that the most common entry under Reaction is “nothing serious happened.” But when something serious does happen, it has to do with legal penalties: “Everyone was detained 3 times. Beatings, harassments, surveillance, slashed tires” or “Detention, day in police station.” And note that the actions include ones imposed on the group’s members, rather than organized by them: “140 Hours of Community Service 2018-19,” “Pyotr’s Poisoning 2018,” and so on.

As MAC director John Zeppetelli writes, Pussy Riot has “used the police state’s apparatus of repression and authoritarianism as a creative partner, engaging in an uneasy ‘dance with the devil.’” This is risky stuff. Prison time adds up, not to mention fines and extrajudicial violence. It takes incredible courage to keep exposing oneself to the wrath of a brutal regime without conscience. But while Pussy Riot’s interventions may be, as the catalog says, “desperate, sudden and joyous,” that joy seems very far away from hope. Does Pussy Riot really imagine that they can change Russia? Or even just change some minds? It doesn’t look that way. These sisters are doing it for themselves: trolling the government, the church, the oligarchs, and so on is its own reward.